Bush patrols were fundamental to kiap administration within pre-Independence Papua New Guinea.

Tens of thousands were conducted over many decades before 1975 and many continued to be staged for several years after,

Some moved through swamps, others hopped by launch between coral atolls and islands, still more followed giant rivers, tramped across vast grass landscapes or toiled over difficult mountain terrain.

But even though they could be quite different in duration, conduct, aim and outcome they had a great deal in common.

This pictorial essay highlights these now historical similarities in unusual detail. Every patrol would have its interpreter, its policemen, standard patrol equipment, its carriers, and most would have camped at a series of pre-determined Rest House locations as well.

So every PNG kiap will recognise routines recorded during this 1974 patrol. Almost all Papua New Guineans born before 1970 will too.

These pictures and their accompanying text also confirm, no doubt to the surprise of many, that this type of colonial administration was still being conducted, not in the late nineteenth century, but at the same time as the first humans walked on the moon and both the Rolling Stones and Daddy Cool dominated transistor radio airwaves.

Indeed many younger kiaps working in the late 1960s and early 1970s wore long hair and sported drooping moustaches modelled on San Francisco hippies.

Tapini Patrol No 9 1974-75 moved through unusually difficult mountain country and the people it met were unusually isolated so in that sense it was not typical.

However, events like the population census, and the village court, were common features of PNG’s cross-national bush administration system and this makes the following first-hand account a valuable historic record.

Patrol details

On December 4th 1974 a routine administrative patrol (Tapini No 9. 74-75) left its Sub-District Office to update census records across the Pilitu section (population just 1,334 people) of Papua New Guinea’s mountainous Goilala region.

It was instructed to:

- Alert the Assistant District Commissioner in Tapini, and the District Commissioner in Port Moresby, to shifts in established population patterns, new developments in economic structure, or swings in social ambition.

- Encourage the people to continue to fall in with PNG law and national aspirations.

- Identify a project that would benefit the people and could be supported through tactically allocated Rural Improvement funds.

- And, just ten months before PNG became Independent, raise the new national flag for the first time at all eight of Pilitu’s established population assembly points or Rest Houses.

It returned on December 12th and, because it was so similar to the many thousands of government patrols that had been launched in all corners of PNG over many decades, it was genuinely unremarkable.

That is except it was accompanied by a casual, non-government, photographer who produced a comprehensive, pictorial record of the regular work still being undertaken, throughout PNG, in 1974 by kiaps (bush administrators or Patrol Officers) overseen by the Chief Minister’s Department just months before national independence.

His pictures underline the character of this regular patrol activity. They also confirm the Pilitu region’s unusual isolation.

The Photographer

Graham Forster (23) was on his way home to the UK after spending 18 months conducting rural surveys in the Solomon Islands when he stopped over in Tapini to visit his brother Robert – the kiap conducting the patrol.

The Landscape

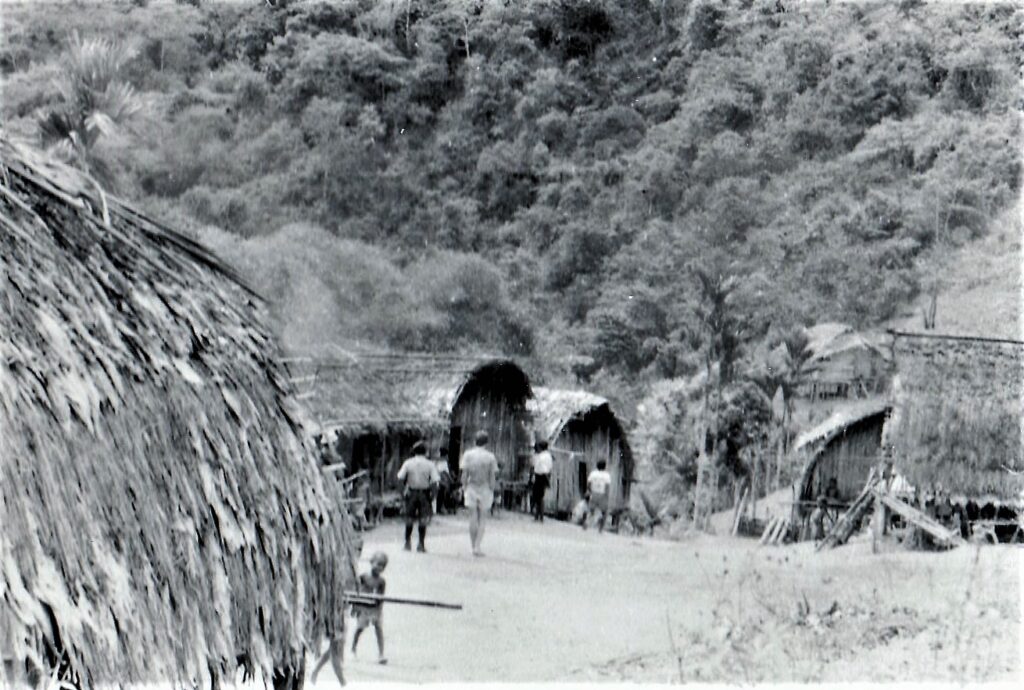

The Pilitu region was the least populated in the difficult Goilala Sub-District. Its mountains were tall, valley sides steep, and fast-flowing rivers had scoured out many gorges.

Therefore, all movement, which was confined to tracks and trails because there were no roads, was a constant challenge.

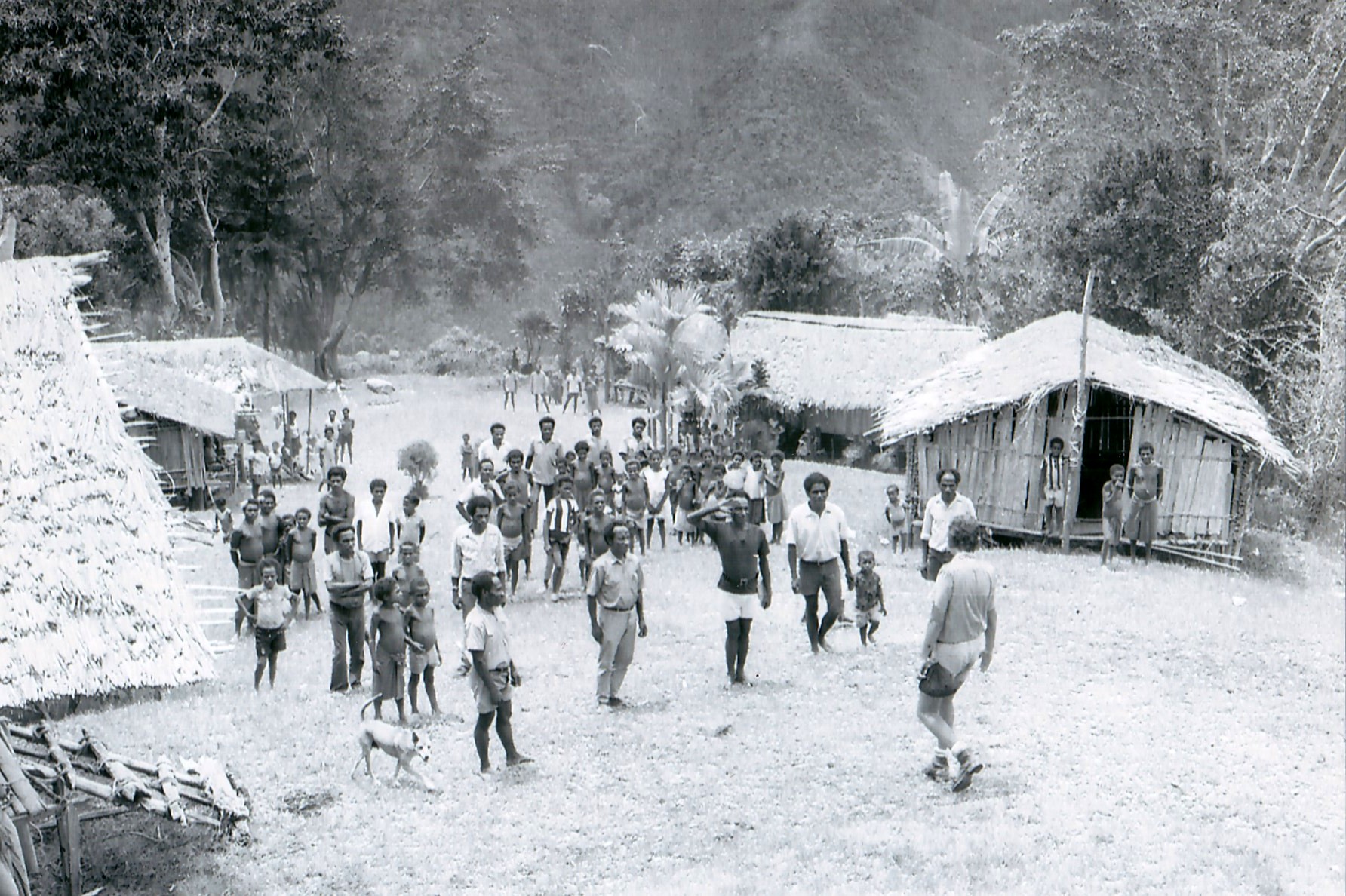

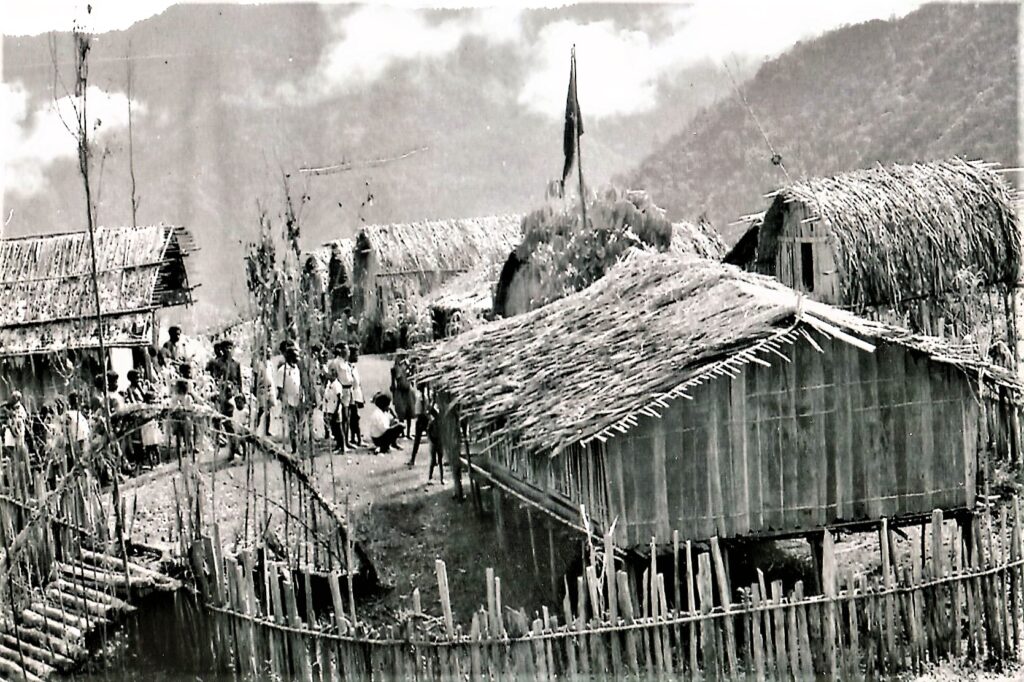

The Villages

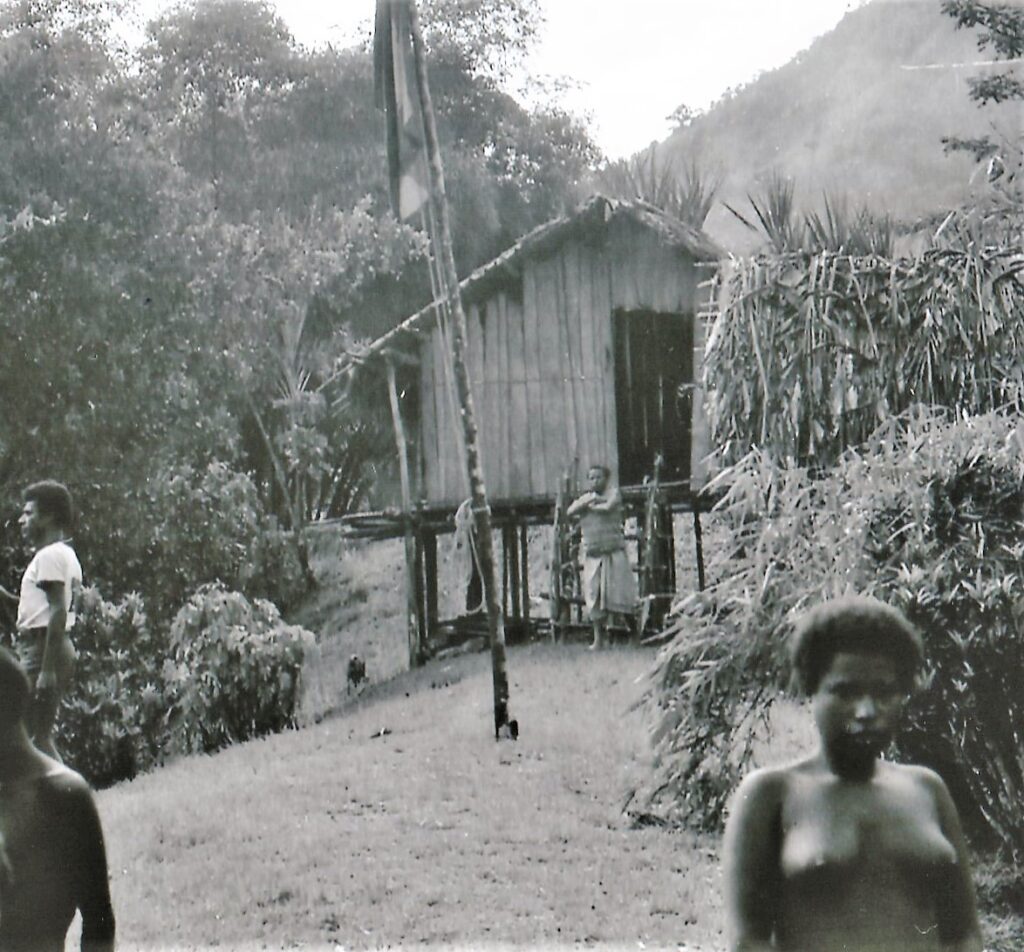

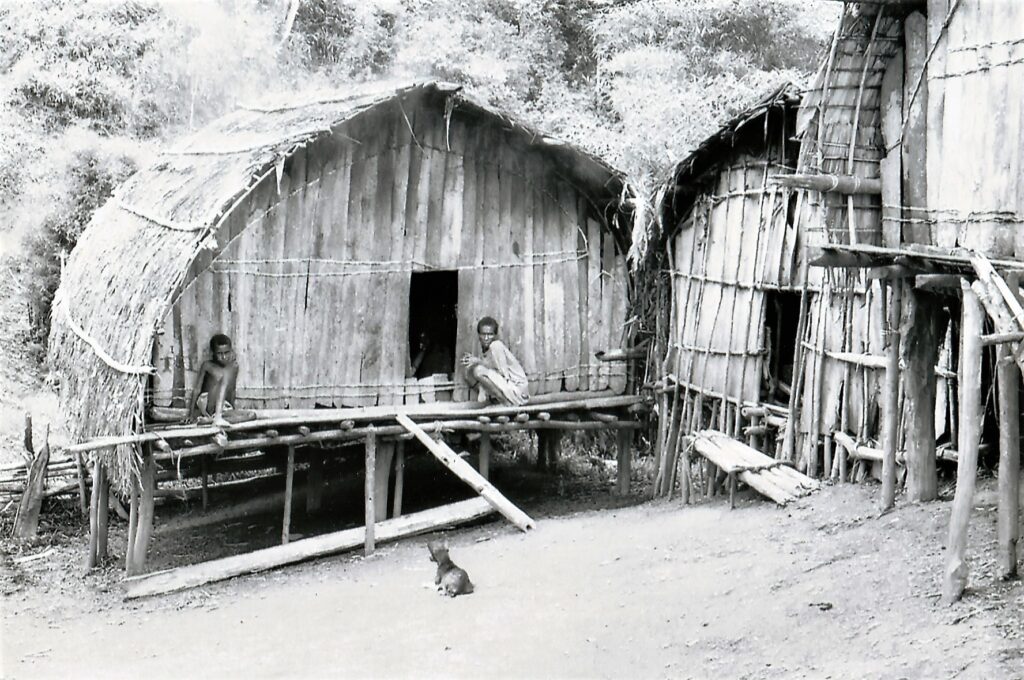

Flat land was so scarce many of its ten villages were strung along narrow ridge tops because they alone offered relatively level building ground. These sites were convenient lookout points too. The people in this village can be seen checking out the patrol’s progress.

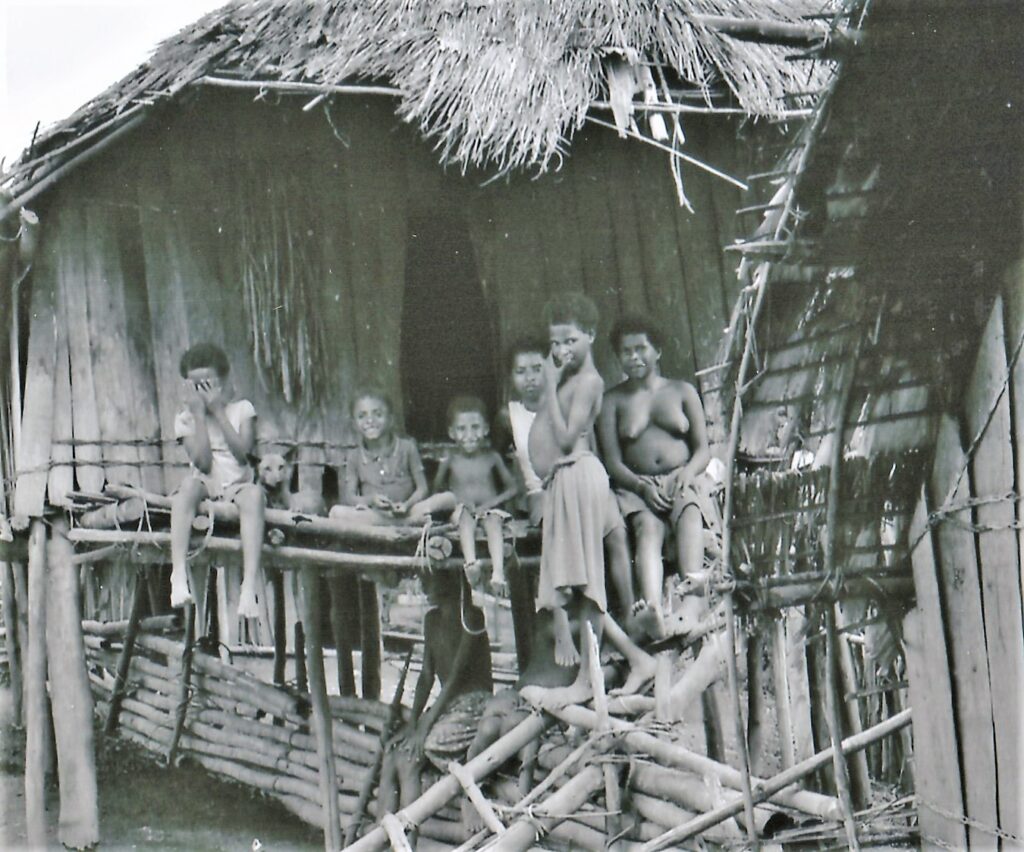

The population of these self-supporting settlements ranged from 274 men, women, and children to just 46.

The Village People

Inaccessibility, both physical and economic, was an unavoidable consequence of their hostile physical environment and the Pilitu peoples’ principal handicap.

They had little opportunity to pursue commercial advancement and so were unusually poor.

Their ethnicity was confused too. Just 1,334 people shared four mutually unintelligible languages – each of them prominent among the much larger communities that surrounded them.

In both aspiration and identity terms, they leaned towards their Kuni neighbours who occupied lower, more accessible, less mountainous land.

However, these were overseen from a separate, and more distant, Sub-District Office at Bereina which was in a central position on the relatively well-developed coast – and not Tapini which was officially charged with their wellbeing.

This generated obvious administrative complications because, even though five of their villages were within one day’s walk of Tapini, the Pilitu people insisted they were not Goilalas.

The children in this picture were not well nourished.

The Isolation

Isolation was physical as well as economic. Cultivation of exotic commercial crops, like coffee, which could generate additional income and reduce dependence on subsistence farming, was made almost impossible by the steep terrain and distance from any market. This has been picked out as Graham’s best photo.

The next generation

Would these youths be satisfied with subsistence farming and a respected place within their community or were their ambitions wider?

Securing an education was not easy. Despite its relative proximity only a handful of their peers took advantage of the primary school at Tapini. Slightly more had attended a more distant Mission school in the Kuni region. The patrol was told that perhaps twenty Pilitu boys attended a secondary school near even more distant Bereina.

Village Leaders

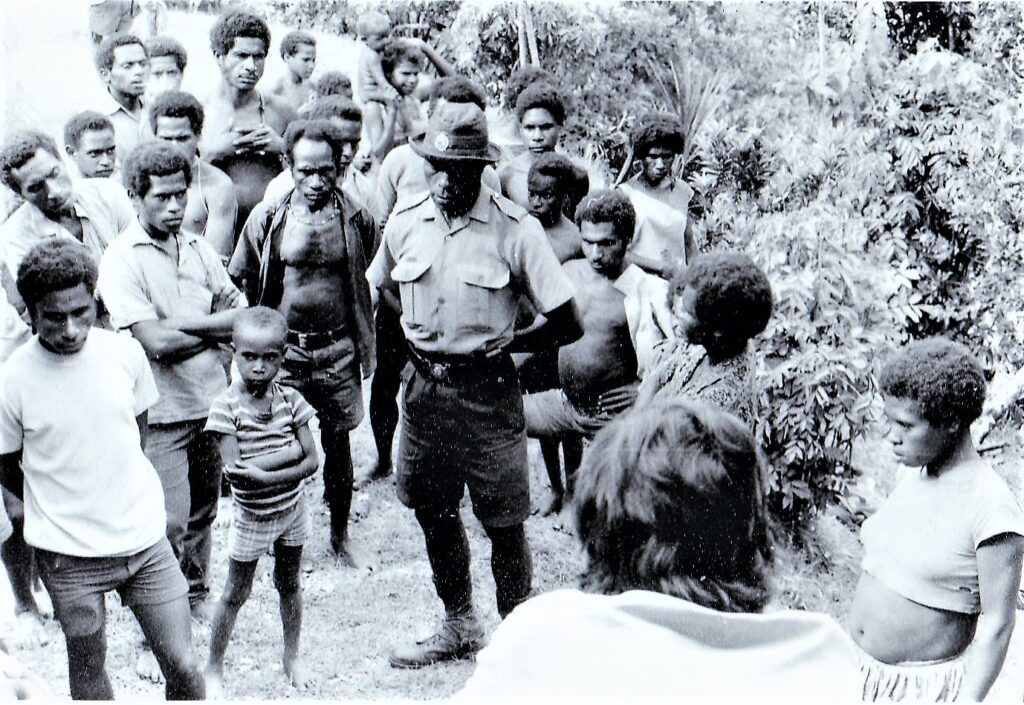

Government patrols could not function without the cooperation of local leaders.

The man in the belted black uniform is the Village Constable who was the official link between the administration and his community. He was paid a stipend for this service.

One of his duties was to make sure everyone came to the census because attendance was compulsory. Others included using his authority to ease minor social tensions and report de-stabilising crimes, like serious physical assault, to Tapini’s Sub-District Office.

The younger man to his right proved to be an effective intermediary for his community when its census was conducted.

The Carriers

Carriers were indispensable. Patrols could not move without them. Like all mountain people the Pilitu were durable, the result of being obliged from childhood onwards, because there was no alternative, to hauling or carrying every item needed to maintain their livelihood or manage their homes.

They could tote often awkward Patrol Boxes (pictured) up hill, and down dale, for hours on end. Shoulders, as is the case here, were protected from being skinned by cloth pads.

Carriers were paid for their services and in the cash-starved Pilitu there was no shortage of volunteers.

The metal Patrol Box, which had a sealed lid to protect its contents, was a standard item of patrol equipment. There was an official weight limit because it made no sense to overload men moving through difficult terrain.

The Interpreter

The interpreter was the kiap’s right-hand man. The linguistic bridge between him and the people the patrol was moving through.

This is Louis Girau. He was proud of his uniformed position, spoke Pidgin English, Police Motu and Tauade (his own Goilala language). The Pilitu people shared three others. Louis would have been fluent in at least one.

During a census he took a position on the kiap’s right side where he would repeat questions posed in Pidgin English that had not been understood and interpret the answers, Accuracy was essential. It minimised confusion, maintained recording accuracy, and encouraged open exchange.

During one-to-one discussion with a village leader, or someone with a specific observation or complaint, who could not speak Pidgin English, accuracy was even more important – as was trust.

A wily interpreter could, because a kiap could not understand what was being said in a local language, tilt discussion if he wished – and some did. The common view was that Louis did not.

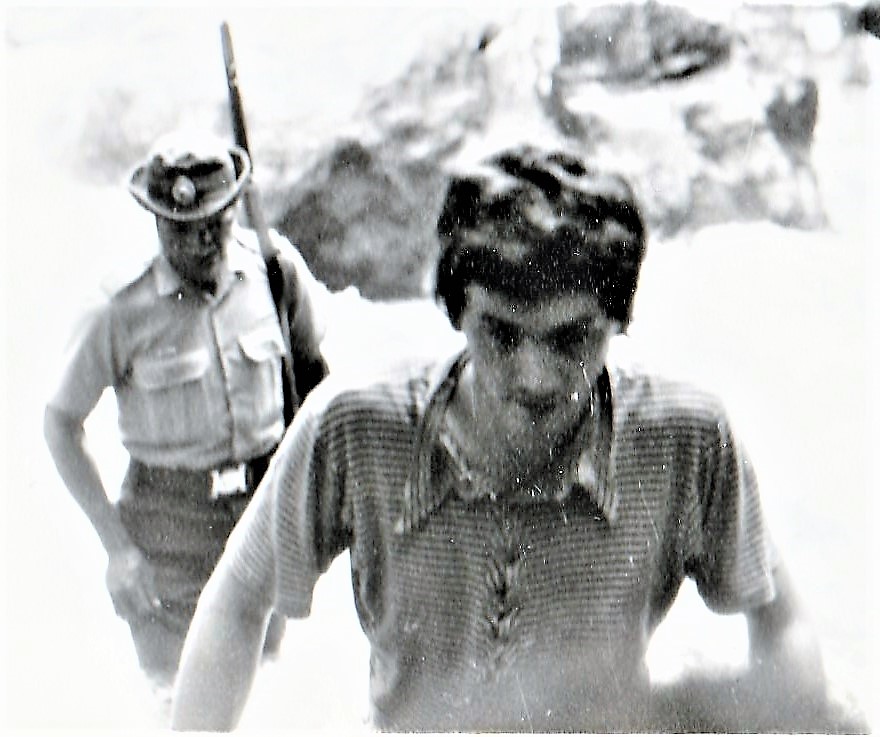

The Policemen

Policemen like Constable Apua (left) and Senior Constable Bakaia (right) were familiar with patrol routines and at ease with the people the patrol was visiting. Their authority was always accepted.

The .303 rifles they habitually carried underlined this clout. Ammunition, should there be any, was always held by the kiap himself. None was carried on this patrol. It would have been unusual if it had been.

Policemen multi-tasked. They helped organise carriers, conduct the census, secure fresh food supplies and made sure the patrol moved freely through interruptions (should there be any) to its progress.

They were also required to be observant, be the kiap’s eyes and ears, and pass back information, on any subject, they thought might be useful.

They could improvise too. For example Apua took it on himself to keep a watchful eye on the photographer – as can be seen in the first picture in this sequence.

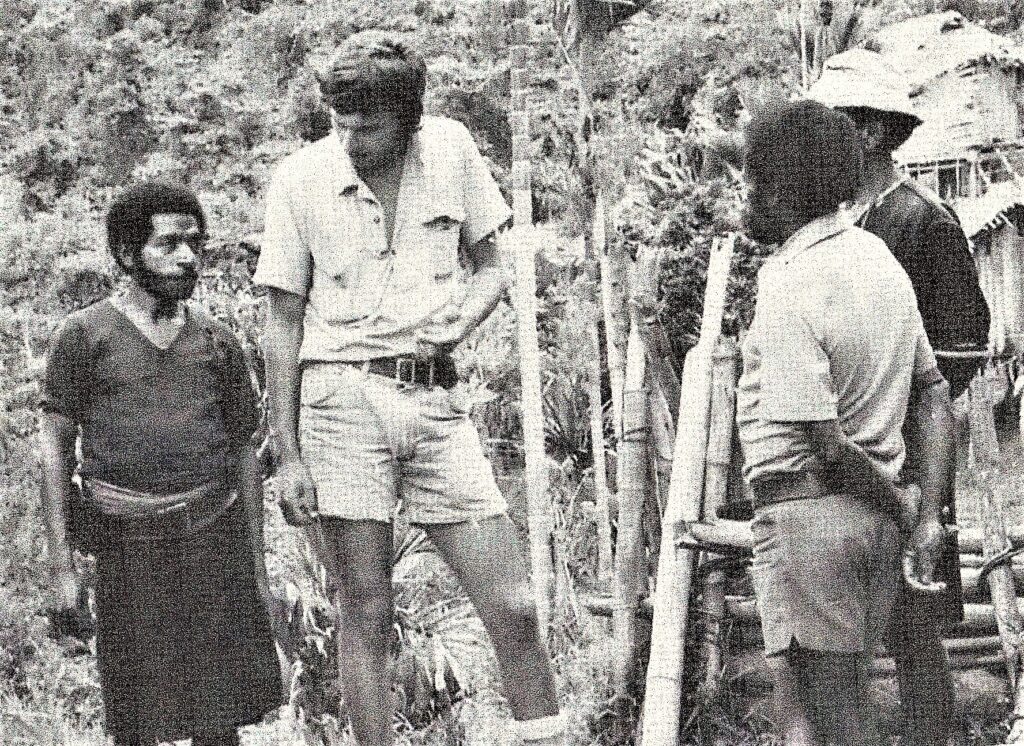

The Patrol Officer

Robert Forster, who was 27, was relatively old for a Patrol Officer. He had worked in PNG’s bush since 1968 and was recruited by Australia’s Department of External Territories in 1971.

He was fluent in Pidgin English and could speak directly to patrol staff and many Piltu men – including village leaders.

However, his Police Motu was poor which was a handicap in the Pilitu where it was preferred to Pidgin.

The Assistant District Commissioner in Tapini was his immediate superior.

Immediately after returning to Tapini, he presented a mandatory Patrol Report to the Assistant District Commissioner. It was forwarded, with additional observations, to the District Commissioner in Port Moresby.

Record of the patrol’s progress

It left Tapini on December 4th.

Some rivers could only be crossed using log bridges.

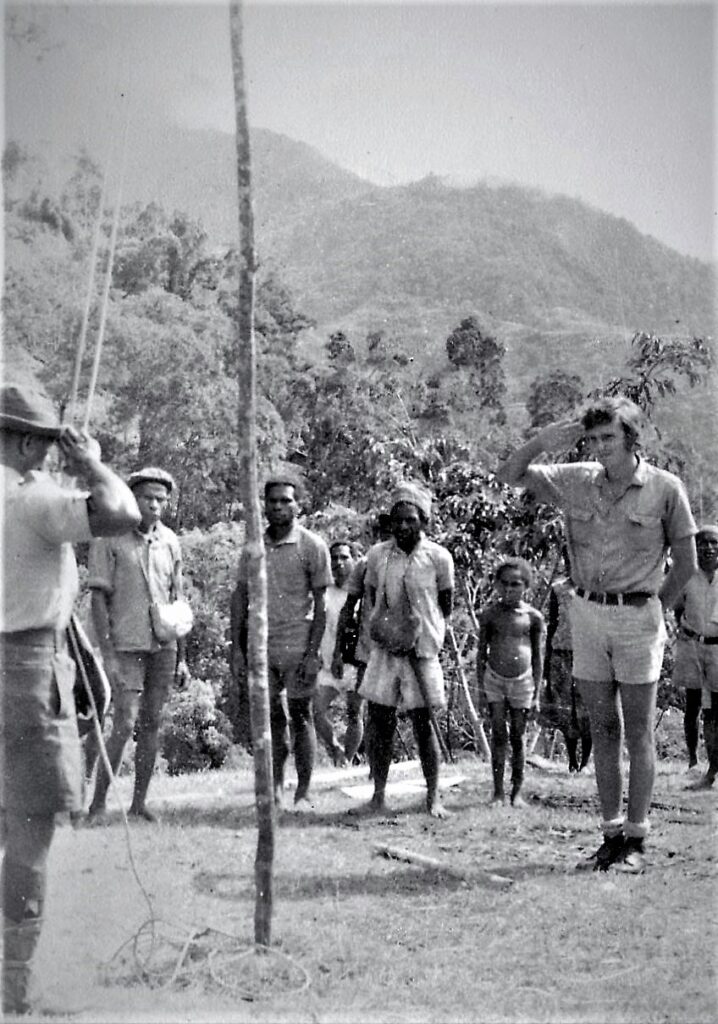

Village leaders would line up to welcome its arrival. This headman’s salute reflects military influence within the emergent kiap service. One man is standing with his infant son. This confirms the mood is relaxed.

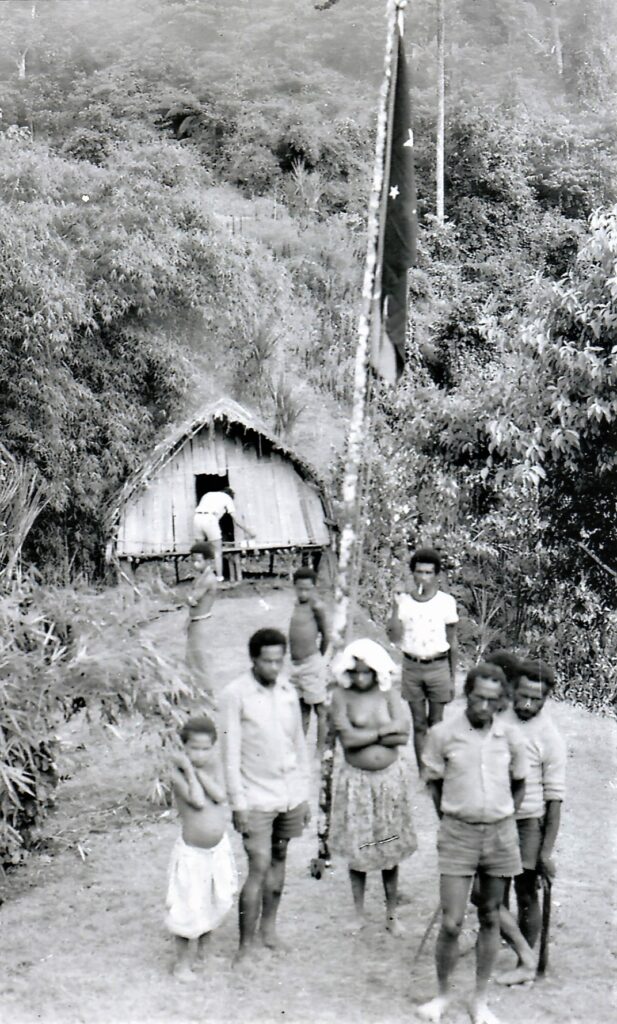

Raising the national flag was every patrol’s first task. It was a formal undertaking that underlined its official status.

On this occasion, the new Papua New Guinea emblem was being flown inside the Pilitu for the first time. It was accepted without question – perhaps because it had been flying outside Sub-District offices at Tapini and more distant Bereina, for many months and was already a familiar sight.

Protocols were strict. The young boy standing at stiff attention to the kiap’s right would have been taught to do so at school. Apua’s salute was parade ground perfect.

The population census

Conducting a census was instructive. There was no better way to measure the mood and general wellbeing of a village group than by working with it to update its records.

Families queued to take their turn in front of the kiap’s table where recent births, marriages and deaths would be logged with occasional comments or notations.

Village people took it seriously. A recent birth could, for example, require confirmation of a new baby’s name which, for many reasons, would be carefully noted by kinsmen and might even prompt nods of approval.

These updates were logged in the official census registers which accompanied the patrol. If someone had died the reason – sickness, accident, or old age – was chronicled alongside their name which was crossed out. This information could confirm recurrent disease or in the case of an unusual number of infant deaths, a hygiene problem with drinking water.

Sometimes a family’s eldest son would appear with his new wife beside him. Her name would be entered with his – with space left beneath for their children.

Conversely, a daughter’s name could be crossed out because she had married and would re-emerge when she lined up with her new family later.

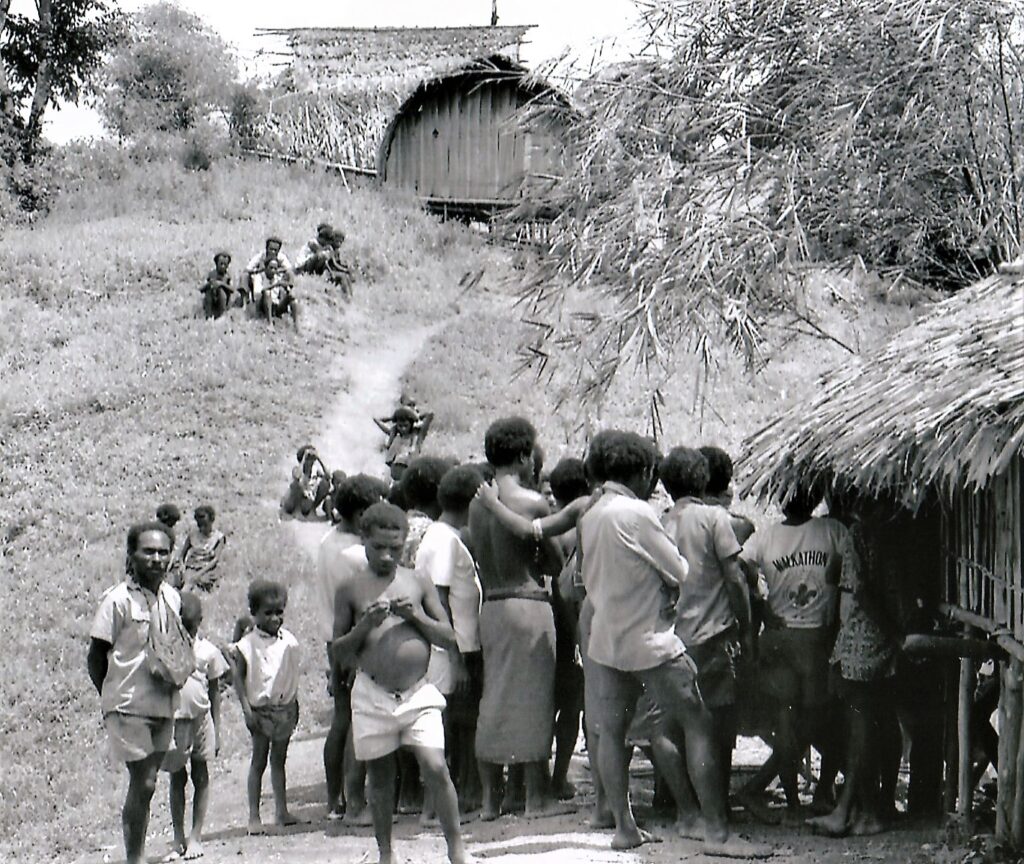

Attendance was compulsory and so a census was almost always preceded by a public information message. On this patrol, the subject was the benefits expected to spring from approaching national independence.

This neat, well-built village was the biggest in the Pilitu and its people were well-organised.

Its perimeter fence was a distinctive feature. It kept out free-roaming pigs which could be unhygienic and destructive.

The census was conducted under the national flag and the queue that had formed was orderly.

The census, which generated a great deal of social entertainment, was the focus of (almost) everyone’s attention throughout the day.

Uninhibited community interest has almost swamped the kiap who is sitting behind the table balancing a census register on his knee. Louis, the interpreter, (pale hat) is to his right. Senior Constable Bakaia is alert. The Village Constable (black uniform – left) stands ready to help. The people are attentive as details outlining the most recent changes to their social structure are confirmed.

The community leader standing on the right held this position throughout the day. He was unusually helpful.

The kiap is struggling to unravel a confusing detail.

Some of the village youths who have crowded the table may be witnessing the transfer of verbal information into formal script for the first time. Others will have acquired elementary literacy at primary school.

And on to next village…

Where….

…the flag was once again raised.

This settlement was unusually small. Nevertheless, the census generated huge interest. It was staged on the only level site able to accommodate a gathering.

And on to next village…

Where…

The Village Constable (left) outlines a difficult social problem. Louis, half hidden by another village leader who is listening in, interprets. It is agreed that an informal village court, overseen by the kiap, should seek a solution.

The kiap (back to camera) conducts the informal court from his hut’s top step. Constable Apua (centre) outlines the problem. The aggrieved complainant stands extreme right. The subdued respondent stands extreme left. Interested villagers, including possible witnesses, look on. Their attentiveness and body language confirm the complaint is serious and a satisfactory resolution is essential.

The issue is sexual. Is it “love gone wrong” or has the young man crossed an established cultural line? There can be no doubt that if this problem is not resolved it could fester.

The kiap will do his best. But his recommendation must be accepted by both families.

And on to next village…

The construction of cane bridges demanded high levels of community co-ordination, practical ingenuity, and athleticism. They were built to last. All the material was cut from nearby bush. Engineering skills were traditional.

Only one pair of men carrying a Patrol Box would cross the bridge at the same time.

Other bridges were convenient but temporary. This carries a man and wife who may be on the way to their food garden. It would not survive a flood.

Where…

The community has gathered to be censused and the PNG flag is raised outside the Haus Kiap.

This village was built along a remarkably narrow ridge.

In 1974 it was unusual for Goilala women to continue to expose their breasts. This confirms the Pilitu’s seclusion.

And on to next village…

Where…

Constable Apua and Senior Constable Bakaia (middle distance) – flanked by Louis the interpreter (left) – discuss a problem raised by the Village Constable (centre).

Three subjects dominated informal conversations with Pilitu people – each of them focused on reducing the impact of their inaccessibility.

The first was ambitious. The construction of a vehicular road linking them with lowland settlements and the more developed coastal region beyond.

The second: the installation of a primary school at a central location within their ethnic boundary.

And the third, equally predictable, was provision of an accessible First Aid Post where routine ailments and minor injuries could be treated by a resident medical orderly.

These children, who were typically undernourished because regular animal protein intake was notably absent from their diet, could not disguise their curiosity.

Senior Constable Bakaia and the Patrol Officer ponder the Pilitu’s long-term wellbeing. “How can a serviceable road be built through these mountains?”, he said. “There isn’t the manpower.”

The patrol returns to Tapini on December 12th leaving…

A community struggling to overcome its mountain barricade.

Villages subdued by their relative poverty.

Listless, undernourished, children.

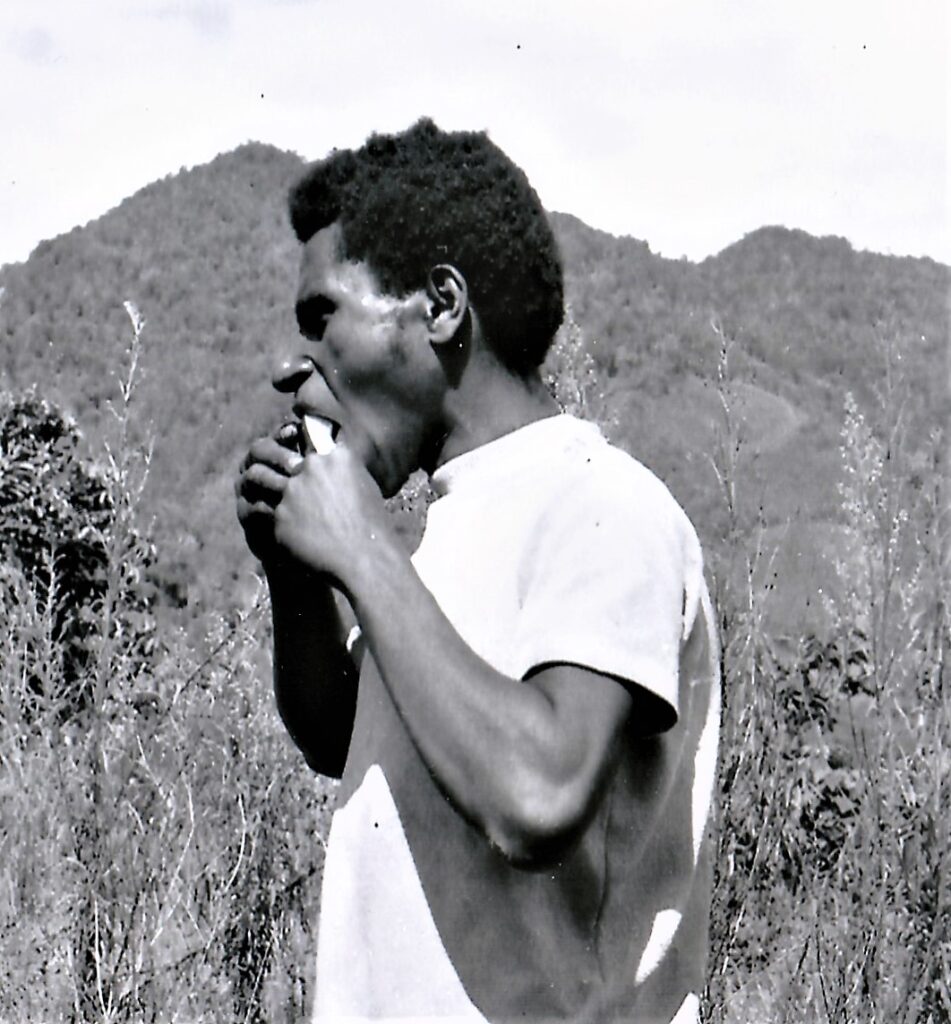

And an optimist playing his bamboo Jew’s harp.

Postscript

The Patrol Officer submitted a Patrol Report after returning to Tapini.

He recommended that construction of a road linking Bereina with Tapini should be adopted as the region’s nominated Rural Improvement project.

The Assistant District Commissioner, who was Australian, told the District Commissioner this was impractical.

The District Commissioner, who was a Papua New Guinean, said the wishes of the Pilitu people could not be ignored.

Each of the Forster brothers returned to the United Kingdom over the course of 1975.

Two Pilitu representatives joined the 13-man Goilala District Local Government Council which is located at Tapini sometime around 1980.

The 96-kilometer, machine-built, often single-tracked, Goilala Highway through the Pilitu, which linked Tapini with coastal Bereina (and beyond) was officially opened in 1986.

It initiated the commercial production, and regular delivery, of temperate vegetables, especially potatoes, from the region to enthusiastic coastal markets.

The road continued to function despite regular problems with land slips and difficult river crossings until permanent maintenance equipment stationed at key locations along the route was withdrawn ten years later.

Government funds began to be re-directed to resolve this problem in 2020. The road can now carry four-wheel-drive Land Cruisers and “10-seaters” but not two-wheel-drive vehicles including PMVs (licensed passenger carriers).

Pilitu children began to attend a new Catholic Mission High School in Tapini in 1994.

A primary school for Pilitu children was built by the Catholic Mission at Lilo village in 2013.

A second was constructed by the Catholic Mission at Kone village, which is closer to Tapini, in 2017.

In 2018 Robert Forster published an account of his bush work in the period immediately before national independence in a book titled “The Northumbrian Kiap”.

Its text highlights several patrols, one of them especially significant and dramatic which spanned 132 days, but there is no mention of Tapini Patrol No 9 1974-75 because its aims and outcomes were unequivocally routine.

@Copyright – Robert Forster