Chapters seven to ten in The Northumbrian Kiap record how kiaps struggled to adjust to the unexpected overnight ascendancy of a national government after the April 1972 election.

Those working in the Minj Sub-District witnessed the impact at village level of sitting MHA Kaibelt Diria’s instant elevation to Minister of State as well.

It was not until 1982 that details covering his dramatic advancement emerged. They are revealing because they confirm that backroom sleight of hand has always been an essential political skill.

One of PNG’s immediate post-election mysteries was how Kaibelt Diria, one-time deputy-leader of the anti-Independence United Party, was persuaded to cross the floor of the House of Assembly and become a Minister in PNG’s first, pro-Independence, government instead.

This update confirms that his fellow MHA, Iambakey Okuk, was an instinctive politician. It may even be that he was the man who gave the post-1972 push for national independence its wheels.

The 1972 election appeared to have produced a predictable result.

The conservative, anti-independence, United Party had secured 37 seats and Michael Somare’s pro-independence Pangu Pati just 18.

The United Party was sure it would form the next government and so were many others.

But the Pangu Pati confounded these expectations by constructing a majority coalition.

Australia’s top man, the Administrator, had to move out of his Port Moresby Office and Michael Somare, who had become Chief Minister, moved in.

This huge political development paved the way to Self-Government just 18 months later and full Independence on September 15th 1975 – which was a great deal sooner than many had expected.

These are the men who became PNG’s first government. They are left to right: Thomas Kavali, Julius Chan, Reuben Taureka, John Poe, Bruce Jephcott, Michael Somare, Paulus Arek, Paul Lapun, Gavera Rea, Boyamo Sali, Ebia Olewale, Albert Maori Kiki, Donatus Mola, John Guise, Kaibelt Diria, Moses Sasakila, Iambakey Okuk. (Photo – Post-Courier)

So how did the Pangu Parti’s coalition secure its critically important majority?

The answer is revealing.

The key players could not have been more different.

One was young. The other much older.

Each was ambitious but had a contrasting take on the rewards of political power.

One was a traditional big-man. The other an itinerant motor mechanic.

One was illiterate. The other had wide vision.

It was the younger man, Iambakey Okuk, who initiated the decisive ploy.

His target was Kaibelt Diria

Photo Robert Forster

The background

Traditional big-men enjoyed traditional support so no one was surprised when Kaibelt Diria was elected to represent the Mid-Wahgi constituency of the Western Highlands in the first House of Assembly in 1964.

In 1968 he backed the conservative, anti-independence, Highlands dominated, United Party which became the most influential parliamentary group.

But immediately after he was re-elected in 1972 he abandoned the United Party, on whose platform he had campaigned, and joined Michael Somare’s new National Party coalition instead.

His defection helped Somare secure a parliamentary majority and paved the way for Self-Government just eighteen months later.

His reward was to be appointed Minister of the Department of Post and Telegraphs – later known as Communications.

His undisguised ambition delivered a chauffeur driven car, numerous opportunities to tour other countries on fact finding missions, and a position in the Wahgi Valley which persuaded Marie Reay, an anthropologist who had worked there for decades, to describe him as its “comptroller general”.

Kaibelt could neither read nor write.

He was knighted in 1983.

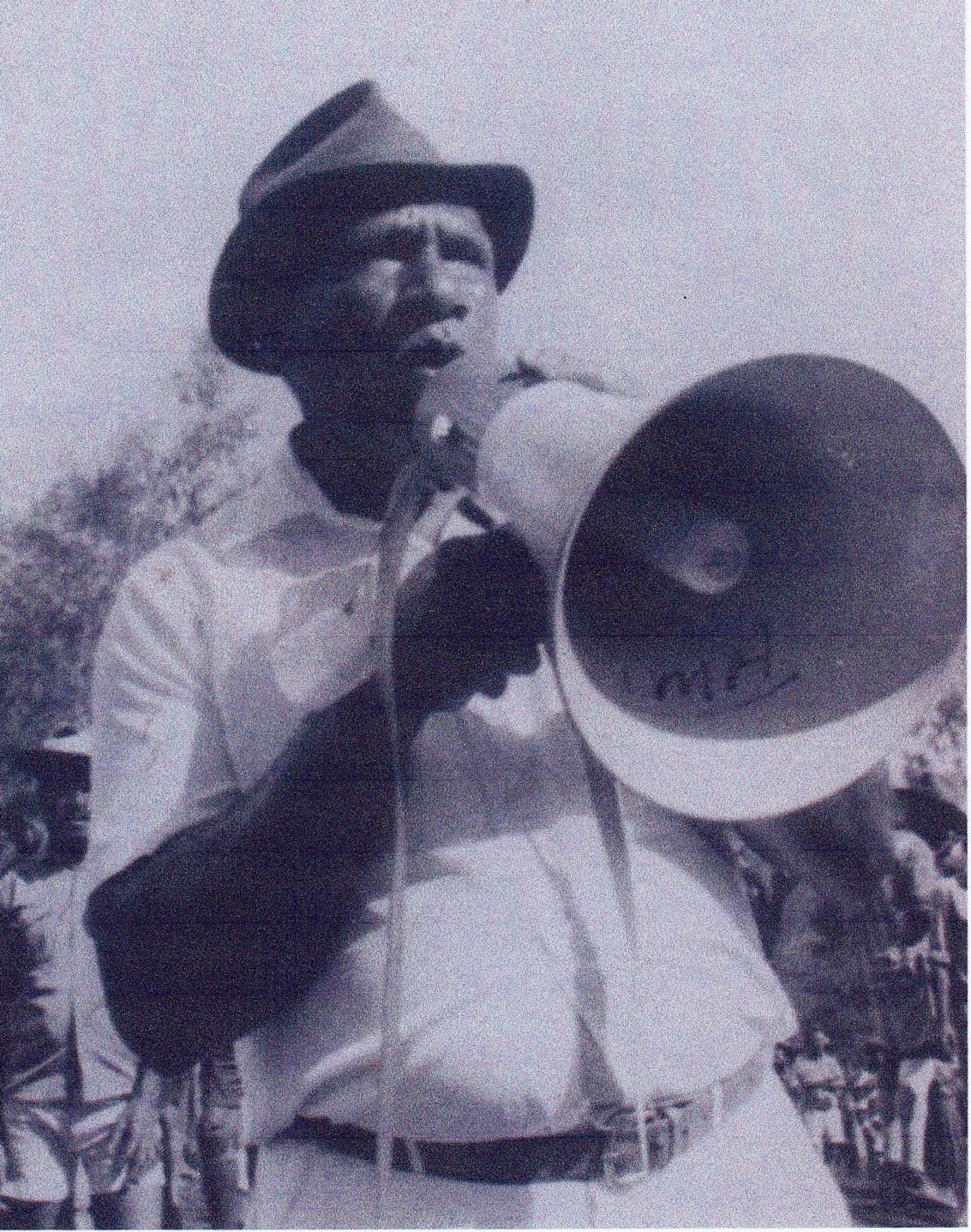

Iambakey Okuk, whose constituency was the Chimbu District, and who had been elected to the House of Assembly for the first time, was not only educated and visionary but immediately proved to be a skilled political fixer.

This is his account of how he persuaded Kaiblet to change sides. It is taken from a tape recording made while he was addressing students at the University of Papua New Guinea ten years later.

“We went and greased up one bloke called Kaibelt Diria. (In Pidgin English, grisim or ‘to grease’ means to trick somebody into doing something through flattery or lies.)

And, you know, we said to him: “Papa, the Australian government has already announced that Somare is to become the first Prime Minister.”

And he says: “What!”

And we said: “Yeah. They announced on the radio that we have already got the (right) number and we’re forming a government.

“But we don’t have enough Highlanders and we want to give out some ministries to some people.”

So we said, “But Papa, there is only a few of us and we are still young and we are looking for some elders (like you) to take the important positions.”

And he said, “Yeah? Wait, wait. OK! (That can be fixed.) We go now!”

And we said, “Look, hang on, hang on, it’s OK. The position won’t run away. You’ll get it. But you must also bring another five (people) or something like that.”

“Oh, that’s no problem,” he said. “I’ll bring seven!”

So he brought back seven (newly elected MPs) and so we made the number.

This is how Somare got self-government.

But we did a dirty job which you don’t know.

I had to tell lies to my old father who had more pigs and more wives than Somare, you know. Many, many wives – many, many pigs. Big coffee plantation – more things than Somare, myself or Chan (another prominent politician) put together.

Anyway, the poor guy, we had greased him so he had to come become a minister.

We made him the Minister for … Telephones!”

Kaibelt’s Ministry, Post and Telegraphs, was an entirely new government department.

Iambakey Okuk was made Minister of Agriculture. He became Deputy Prime Minister in 1980-82 and was Leader of the Opposition in 1983-84.

He died suddenly in 1986 aged 41 and is still regarded as one of the most influential of Papua New Guinea’s post-independence leaders.

Kaibelt Diria lost the next (1977) election to Talu Bol whose arrest by the author for riotous behaviour (inciting a traditional fight) in 1973 is described in chapter ten.

@Copyright – Robert Forster