My review of The Sky Travellers was posted on the PNG Attitude blog and the Ex-Kiap website on March 16th 1921. The book offers the best summary of pioneer exploration in the Papua New Guinea Highlands on record.

It also underlines the bureaucratic tussle between bush kiaps (kanaka men) and the white supremacist bureaucrats who controlled them.

My sympathies are of course with the Kanaka men. Even as late as 1970-75 whiffs of white supremacy still lingered within the kiap service and although I was fortunate to have worked with many first-class senior officers there were others who were bureaucrats to their core.

I worked in the Wahgi Valley for 18 months over 1972-73 and while there was in charge of a 132 day patrol which flew the new Papua New Guinea flag for the first time.

It was entirely coincidence that it moved through the North Wall using bush paths taken by the legendary kiap Jim Taylor when he passed through on his 1933 exploration.

Nevertheless this was considered significant by the Wahgi people and my patrol acquired unusually high status – possibly because it too was heralding substantial change.

Confirmation of this came with the posse of old luluais it began to trail, each of them with his own story about Taylor’s arrival, then the increasing mountains of food, including pigs and other traditional gifts, offered by the host clan as local custom began to shape the welcome surrounding its arrival for a 4-5 night stay.

During the evening the appearance of, reaction to, and consequences that flowed from “Jim’s” earlier arrival dominated informal fireside conversation. It was, without doubt, the most critical event of their lives.

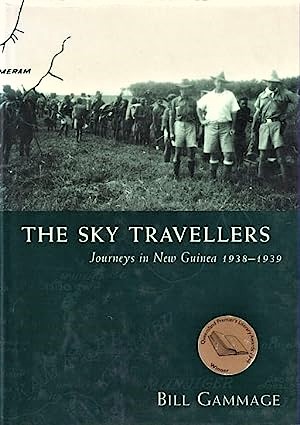

And so I’m pleased to have just finished reading Bill Gammage’s “The Sky Travellers”, which focuses exclusively on the Taylor-Black 1938-39 Hagen-Sepik patrol.

I put it down thinking it is best of many books that set out to describe early kiap contact work in PNG.

This is because Gammage is unflinching his description of attitudes surrounding highland exploration and, among many other things, underlines a destructive civil service rift between the unadulterated white supremacists who dominated senior colonial administrative positions, and those who were pro-native, the so-called “kanaka men”, who were dominant among the kiaps who were somewhere “out there” breaking bush.

Speaking as a Pom, and this is a personal aside, I have always found it strange that Australia, home to the legendary, fiercely independent, outspoken bush digger, also spawned a civil administration system that was often unnecessarily fussy, mean-spirited, and narrow.

So it was disappointing, although perhaps not a surprise, to discover that in the post-war administrative turmoil that brewed in 1945, it was the white supremacists who won.

Most of them were adept paper shufflers, desk men, masters of the damning footnote, and so pro-native protagonists like Taylor and Black who loved the bush, were excited by its people and could not wait to “get back out there”, were outmanoeuvred because their minds, and hearts, were elsewhere.

As a result, despite conducting a uniquely demanding, and successful, fifteen-month first contact patrol, something that in terms of length not just in time but miles covered, was matchless within in PNG, they were in Black’s case deliberately steered away from Highland areas or in Taylor’s only able to return after accepting unwarranted, possibly spiteful, demotion.

Moreover their patrol reports were astutely hidden in a “not important” drawer so their references to Telefomin and other potentially difficult areas were not available to those who came later. Was this the result of vindictiveness, pre-occupation with urgent post-WW2 demands, or culpable failure to recognise the patrol’s importance?

For its author, Professor Bill Gammage research for, and assembly of, The Sky Travellers must have been a labour of love.

It took him thirty years over which he used his dual positions at Australian National University and The University of Papua New Guinea to good effect because over 100 Papua New Guineans, many of whom either worked with, or were contacted by, the Hagen-Sepik patrol are listed among first-hand informants that include Taylor and Black themselves.

He does not pull punches. He is clear that one of the costs of first contact was the death of some suspicious villagers through gunfire – even arrows.

Nor does he brush aside the rape of some women, the theft of pigs or other food, and the looting of some property.

The patrol was immense. It is estimated that over 350 people walked with it, most for its duration, and only handful for less. No wonder it was viewed by some administrators and many wary Papua New Guineans as an “invasion-sized force”.

Its personnel included 38 policemen, perhaps a dozen cooks and somewhere in the region of three hundred carriers – all of whom had to be sheltered, protected, and fed.

Gammage unwaveringly examines the logistics of maintaining and disciplining this multitude in difficult, often hostile, country. His observations are always revealing.

His consideration of Taylor and Black is diligent too. Taylor is confirmed as a genuine explorer, a man who relished adventure and the challenge of successfully overcoming initial village resistance to his presence and establishing genuine inter-personal relationships instead.

He is definitely a “kanaka man” and Gammage repeatedly underlines that Taylor was able to recognise that despite their lack of global sophistication the Papua New Guineans he met were proud, self-reliant, well-organised people with an admirably independent approach.

He saw “kanakas” as yeoman, a term most often used to describe an unfettered, land-owning, British villager in Anglo-Saxon times, not as a man without merit or worth.

If I have read the text correctly Black began the patrol with a foot in the white supremacist camp but emerges a fully-fledged, pro-native, kanaka man instead.

Gammage attributes this to his unrelenting exposure to Papua New Guineans reacting to a range of demanding conditions and at no point is this made clearer than Black’s distress at having to abandon Babinip, a young girl from Telefomin, with whom he had developed a tender relationship, when the time came to move his section of the patrol irrevocably on.

It is striking too that in 1946, when the names of many people in large sections of the Highlands had still to be listed, Taylor was so impressed with those he had met he was already speculating, on record, about the likelihood of them eventually being able to cast off control by Canberra and become politically independent in their own right.

Was this another reason that after his wartime work was over he was demoted by well-placed, white supremacist, administrators and eventually gave up kiap duties altogether?

The Sky Travellers, Professor Bill Gammage, Melbourne University Press, First published 1998.

@Copyright – Robert Forster