I was the last European kiap to be posted to Guari. More detail covering this period can be seen in chapters fifteen to seventeen of The Northumbrian Kiap.

The station was positioned on the northern fringe of the difficult Goilala Sub-District and had been given Patrol Post status at the end of World War Two.

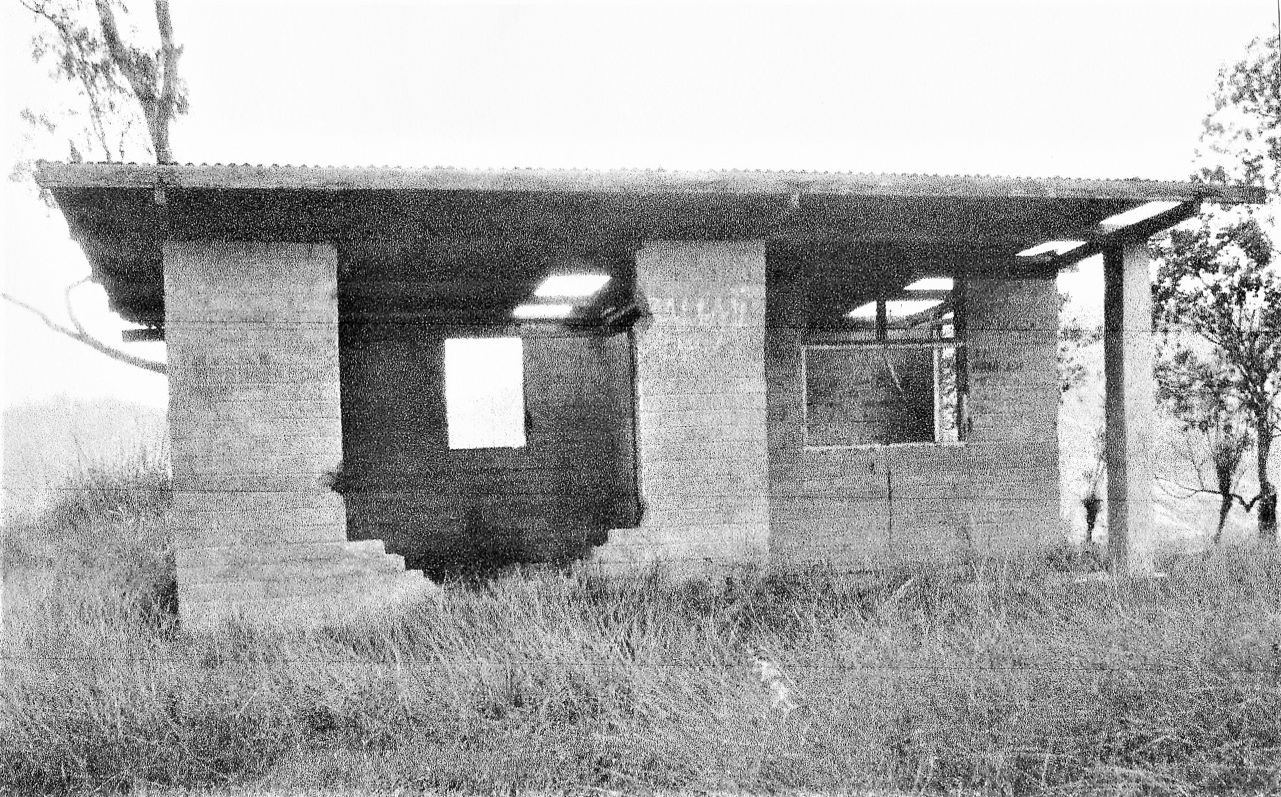

However, construction of a permanent administrative complex, with a home for the resident kiap and an office for his staff, did not begin until 1966-1967.

Work on the adjacent airstrip (below) began in 1964 and was completed in 1970. Its altitude is almost 7,000 feet.

(Picture: Anthony Morant)

The Patrol Post was abandoned almost exactly forty years later.

An influential Catholic Mission, established at nearby Kamulai in 1947, was abandoned in 2014.

This means the region’s Kunimeipa people have no regular contact with Papua New Guinea’s government, nor a mission station, and live in what can only be described as a no-go area.

Their population was estimated at 5,340 in 2000. This has been disputed with estimates as high as 14,000 advanced by some as an alternative. There is no way of knowing which figure is correct.

The Kunimeipa’s daunting mountain ranges were one of its problems. Its astonishingly high murder rate was another.

Tit-for-tat pay-back killing is embedded in Kunimeipa culture. Its pre-1945 murder rate was estimated at 60 victims per 10,000 population each year.

Government efforts to suppress it were not successful until 1950 and even then required unusual ruthlessness.

Patrol Officer Roy Edwards has been credited with single-handedly imposing an almost total reduction.

He was an uncompromising man who criss-crossed the Kunimeipa for months on end in an ultimately successful effort to erase its entrenched pay-back spirals.

He and his policemen are pictured (below) with a line of manacled Kunimeipa prisoners after he completed one of his regular anti-murder patrols sometime in the late 1940s.

(Photo made available by Paul Edwards)

His single-mindedness and durability opened the way to improvements in village wellbeing and opportunities for economic development.

However his methods, which focused on threat and coercion, were brutal and in June 1950 he stood before the Supreme Court after being charged with common assault.

He was jailed for six months then left the Department of District Administration, which was keen to move on to its next, economic development-focused, phase.

Although Edwards was officially disgraced his murder reduction tactics were so successful long-serving priests stationed at Kamulai in the 1970s openly credited him with saving hundreds of lives.

His unbending efforts are now thought to have delivered perhaps forty years of relatively murder-free security for the Kunimeipa people.

The positive impact of the Catholic Mission at Kamulai

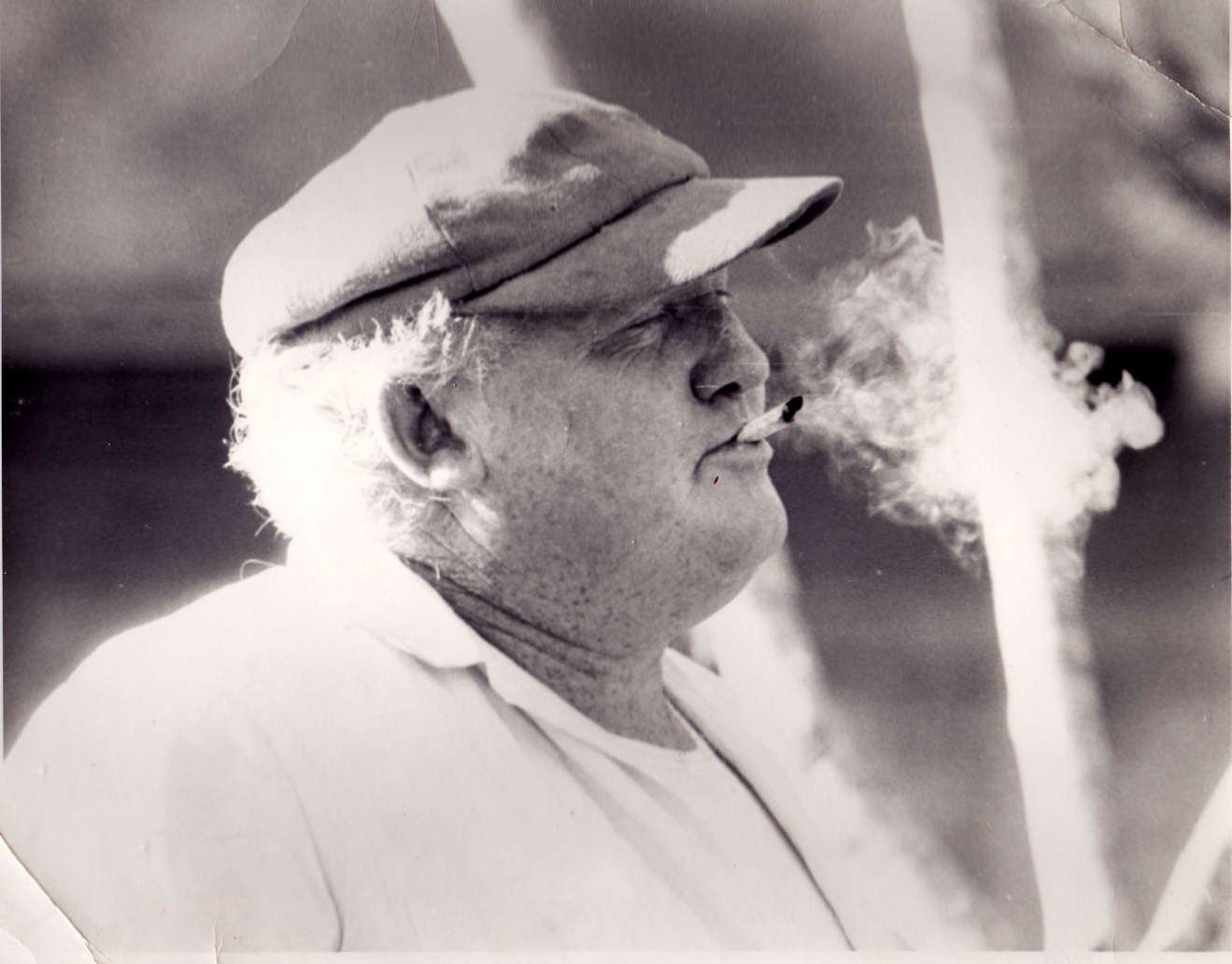

The man in the photo above is Father Abel Michenaud. It must be obvious he was a Frenchman. He was just as enthusiastic about his evening glass of rough vin rouge as he was about his ubiquitous cigarette.

He was born in time to be inducted, in his teens, by Nazi invaders as a forced labourer in one of many notorious “slave camps” near Nantes.

As a result Abel came to PNG no stranger to violence because the daily trek to his slave work, flanked by armed Nazi guards, regularly involved stepping around fresh French corpses that has been shot overnight.

He became a priest and in 1973 was in charge of the Sacred Heart mission station at Kamulai.

Father Abel worked with his hands. He cut timber to build school classrooms, held a gelignite blasting permit which made him indispensable to local road construction, and oversaw a cattle breeding project which he hoped would eventually become a mainstay of the Kunimeipa economy.

In 1975 the mission at Kamulai also supervised schools, stocked the region’s only wholesale trade store, and managed a valued cluster of outlying medical aid posts.

Its presence was critical to the Kunimeipa’s wellbeing.

Abel died at Kamulai and was buried in its church. When it was being built he had asked for the concrete floor at his chosen spot to be unusually thin because he did not want those who dug out his grave to face unnecessary hard work.

Critical signs of fundamental administrative decline

In February 1975 I was told to take over Guari Patrol Post. This a record of my wife’s reactions.

“Paula had already been to Guari where she had seen that the radio and electricity generator were broken, the insecure house was in poor repair and the only regular plane landed on Wednesdays.

We had two children, one almost three years’ old, the other seventeen months, she was expecting her third four months later and the low cloud that often barricaded the airstrip meant it could not be relied on in emergencies.

Compounding these fears the nearest radio, the nearest Europeans, and the simplest medical help, were at Kamulai which was ten miles, or an hour’s drive, away on a difficult road that frightened her and I would be on patrol for at least a fortnight every six weeks or so leaving her alone and unsupported.

She refused to go.”

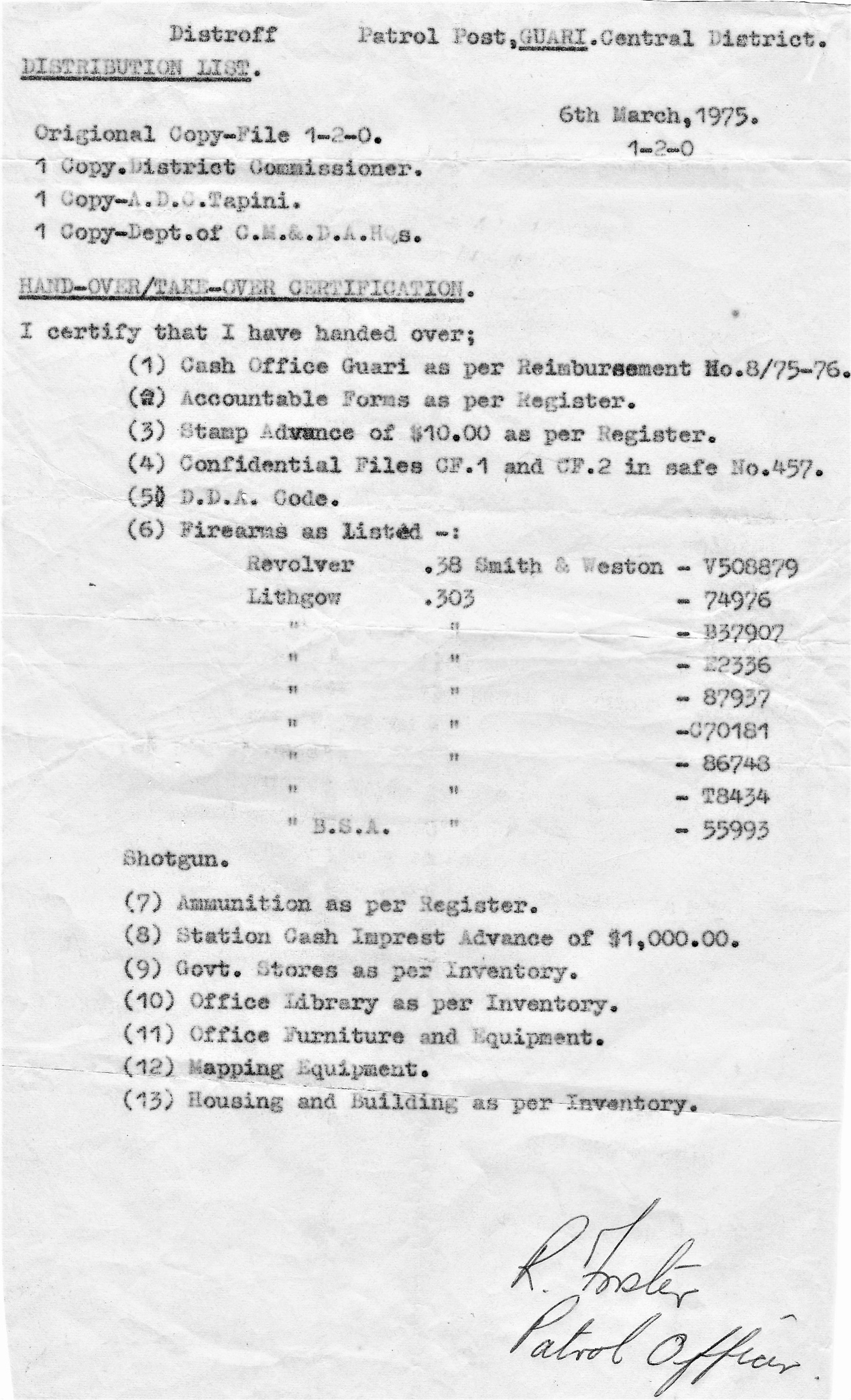

Paula returned to the United Kingdom. I took over as OIC Guari on March 6th1975.

The station was staffed by an office clerk, four policemen, an interpreter, and a tractor driver. Casual labourers were hired for maintenance and other work.

A copy of the Take-Over certificate is posted below.

These were my observations.

“Guari was not thriving, its road system was disintegrating, airstrip maintenance had fallen away, I had to work hard to revive morale and came back from my first patrol to find my house had been burgled.

This break-in underlined Guari’s advancing insecurity.

It was difficult to see how this could be reversed so I decided that the long-term economic wellbeing of the Kunimeipa region was more likely to be reinforced through the Catholic Mission at Kamulai than by the Patrol Post itself.

It had already built, and staffed, several schools, the largest of these at Kamulai itself.

There was no trade store at Guari but the stockroom at Kamulai distributed a wide range of general merchandise, including clothing, soap, kitchen utensils, tinned fish, and tobacco, to both village people and government personnel.

It also ran an aid post which was able to cope with ailments or injuries beyond the experience and skill of government orderlies at village aid posts, was home to the only two-way radio in the Guari area and ran a pair of four-wheel drive vehicles.

To confirm its position as the single, most positive, economic force within the Kunimaipa the Mission had also, with the help of funds from PNG’s Development Bank, initiated a large-scale project to introduce villagers to the practicalities of raising cattle.

It owned, and operated, two air compressors which powered the pneumatic drills it used in road construction too.

In truth, the Mission at Kamulai was, in almost every aspect except policing and formal administration, the model of a vigorous Patrol Post.

I had just four months before I returned to my family in the UK so I consigned the future of the failing road (pictured) that linked Guari with the Sub-District office at Tapini to luck and good fortune and concentrated on reinforcing the link between the airstrip and the Mission at Kamulai instead.

It seemed obvious there was no better way of contributing to the long-term welfare of the Kunimeipa people than making sure the road link between Guari’s airstrip and the mission station remained open for as long as possible.”

The writing was already on the wall.

This picture of the Patrol Post’s long abandoned administrative office, my desk faced the largest missing window, was taken in 2011 by Anthony Morant for his Goilala District Development Blog.

Endemic pay-back killing hits Kamulai Mission when its priest is murdered

The Roman Catholici Mission continued to thrive for many years after government influence declined.

But it too was overtaken by the Kunimeipa people’s entrenched pre-occupation with murder when in May 2014 the priest at Kamulai was shot while holding his regular Sunday morning service.

Father Brian Cahill of Sacre Coeur, who was helicoptered in from distant coastal station at Bereina, wrote the following account.

“It took a week to confirm the death of Father Gerry Inao and several other victims of the pay-back killing spree at Kamulai.

I received a report by telephone on Wednesday May 7th from our Guarimeipa primary school head teacher, John Hoviai, that Father Gerry Inao and the communion minister, Benedict, had been shot dead at Kamulai the preceding Sunday.

John had walked down from Guarimeipa to Zania, where there was Digicel mobile reception.

His report was brief and sketchy: Father Gerry’s body was still on the ground at Kamulai where they shot him as was Benedict’s, whom they had cut to pieces.

Father Gerry, a native of the area and a member of the Kunimeipa tribe, was in his early forties and had been ordained in August 2013. He had been shot through the heart at close range.

A related cycle of pay-back killings has been moving through the Kunimeipa area for more than four years. Reports coming into the government station at nearby Tapini since Father Gerry’s death suggest seven other people have been killed since Sunday.”

The Mission at Kamulai, which was already in decline, was abandoned not long afterwards.

Its closure confirmed that the Kunimeipa, theatre of a long struggle by government to extinguish its endless cycle of revenge killing, and then both government and mission to install essential infrastructure like airstrips, roads and a school, had been forsaken and left to regulate itself.